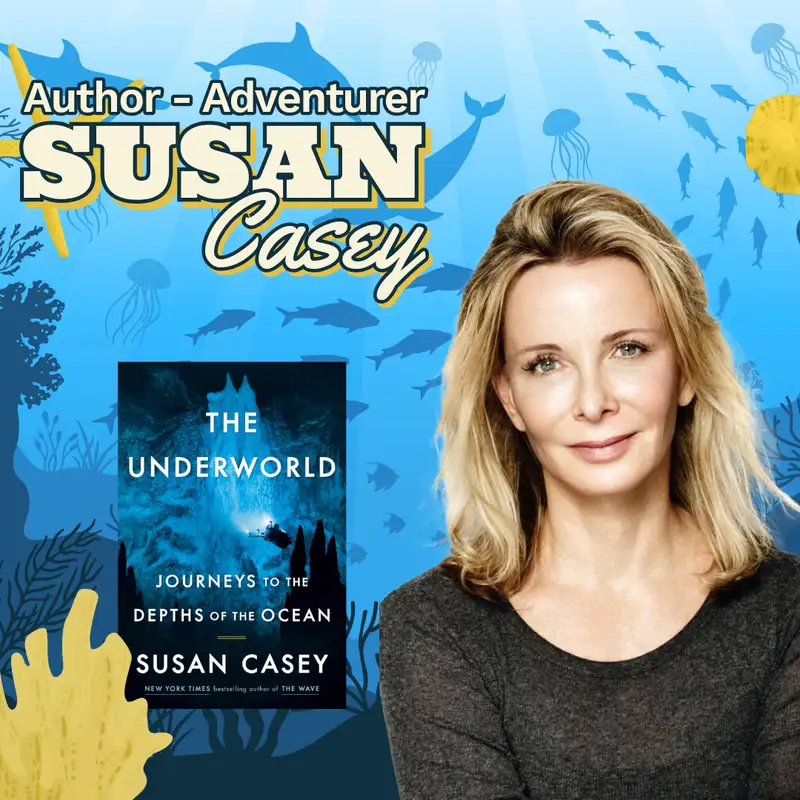

Susan Casey - Adventurer- Author of The Underworld

>> Jeniffer: This is going to be an extraordinary conversation for

me, and I'm going to be honest with you,

I'm a little nervous about getting it wrong because I learned

so many amazing things in this

stunning, work. It is one of the most beautiful books

I've ever readdeveloped. Susan writes

with, you know, like, some books are lyrical

and poetic. This book is

musical. It's written with

so much love and emotion that I just absolutely

fell in love with the deep. Learned so much

about it. So thank you for being here,

and thank you for your extraordinary

ability to make something so unknown,

tangible, bringing it to us.

>> Susan: thank you so much, Jennifer, and thank you so much for coming.

I'm really looking forward to speaking about this.

I always think of anything I'm writing about

as, like, I'm at.

I'm a curious person who goes out and finds cool

things. And then I feel like a ten year old kid in a

treehouse and just wanting to call

other curious people into the treehouse

to say, look. Look at this. I mean, look what this

is. Can you believe we didn't know about this?

>> Jeniffer: It's a total call to the curious. And

it's such a cast of characters in this book who are

all drawn by the same thing. This curiosity

to the deep, this thing we don't understand.

Speaking of ten years old, so you

grew up in Toronto, nowhere near the deep,

as it were, and you didn't even start

swimming until you were ten. Is that true?

>> Susan: That's true. by the time I was 14,

I was at the. I was competing at the national

championships. So it was a question of just

diving in. And, I mean, I was always completely obsessed

with water. And we, had a summer place

on a lake. Canada's full of lakes. And

north, of Toronto, there are these lakes that are very dark.

The water's very dark. And I would just sit for

hours and hours and hours on the dock and hope to see a.

But I was at the same time fascinated and

terrified of them. so I think my

swimming career was a little bit late in getting started because

it was just a question of. I was scared.

>> Jeniffer: Speaking of fear, on page four, which

I should have marked it in advance, I think I want you

to read it. There's

this piece where you talk about

astonishment,

the emotions, starting here. Do you want

to read that for us? Starting with, the

inaccessible way. Yeah.

>> Susan: So before I read this, before I read this, let me just

sort of connect what I just said about these lakes.

Because obviously, growing up in Canada, I didn't

have access to the ocean. and yet these

lakes, whenever I would see a fish, and there are some quite big

lake fish in Canada. I mean, there were fish with.

Does anybody know a musky, if there's anybody from the

east? there were muskies. And every so often I would

see something big and it would just kind of come up from

below. And it occurred to me really early

on that there was like this parallel universe

beneath the surface and we couldn't see it because these

waters were, they're not like some clear

waters, they're like very dark and you can't see the bottom.

And I just remember thinking anything

could come up from there. And that was

so compounded later in my life when I ended up at

the Farallon Islands writing about the resident great white sharks

there. the farallones, was that on

massive steroids. So here was this very

dark, inscrutable water and a great white shark would

pop up or a blue whale or some

kind of, creature I'd never seen before.

And that's when I really started thinking this is

a massive environment. Massive. I

mean, we think of the Earth as being a very large place.

And it is often said that 70% of the

planet is covered by ocean. But what gives

you a better sense of just how immense

the deep ocean is, is if you think of Earth as a three dimensional

living space, a biosphere, 2%

of that is land. Everything we see, everywhere we

live, all of that 2%,

98% is salt water, is

ocean. And 95% of

that 98% are waters below

600ft, which is water that

scientists define as the deep ocean. So

the fact that we don't know, we cross

the surface, we see a little bit in the sunlight

zone, small fraction of the ocean, the ceiling

of a room, right, a giant room.

I just always could never look at any body of water

from Canada to the farallones to

beginning to work on this book and not wonder, like, what's

down there. And, at this very moment,

it's exciting because we are really the first people to ever

have the technologies and the ability to find out.

Jules Verne had to make it up.

>> Jeniffer: And it's really only recent, totally recent.

>> Susan: We are like, if I had written this book, two years

earlier, it would have been obsolete almost

immediately. Because while I was reporting it in the

beginning, there was. We can talk about this

more specifically, but there was, a vehicle, invented that could

go to full ocean depth safely,

repeatedly, with a passenger, a

pilot and a scientist, or a pilot and a journalist in

my case. And that changed everything.

>> Jeniffer: And what year was that?

>> Susan: That was 2019.

>> Jeniffer: Incredible.

>> Susan: Yeah. So now I'll read this because I think I wanted to

give it a little bit of context.

>> Jeniffer: Okay. Thank you.

>> Susan: Yeah.

But the.

>> Jeniffer: You're welcome to start from.

>> Susan: I'm just looking to see if, But the inaccessibility of

the deep, I thought, made it even more

alluring. Others wanted to visit

Paris. Bora Bora, the Serengeti.

I wanted to go into the ocean's abyss.

The idea of an unknown aquatic

realm ever present below us, but

invisible, unless we look for it. An

underworld within our world

had always worked a sort of spell on me, an

alchemical mix of wonder and fear.

It may seem as if those emotions would cancel each other

out, but the opposite is true. When you add

them together, you get the sublime, which

transcends both the

passion caused by the great and sublime. In

nature is astonishment,

wrote the 18th century philosopher Edmund

Burke. And astonishment is the

state of the soul in which all its motions are

suspended with some degree of horror.

But, he added, it was a sort of delightful

horror. The abyss might be

terrifying, but you wouldn't notice because you'd be too

busy gaping in awe.

>> Jeniffer: Yeah.

>> Susan: At least that's how I imagined it. And I wanted to see

if I was right.

>> Jeniffer: Isn't that beautiful? I read that a couple of times.

I was like, oh, my God, this is. You just have

this ability to pull us in.

But let's go back to the beginning, as you did in this

book not too long ago. We knew

nothing of the deep. We had no ability to go that

deepen. And people were starting to. So

you bring us back to the history and the first

pioneers, Aristotle being. I

learned quite a bit. Aristotle, pliny the

elder. And, you know, people were afraid of the ocean,

these monsters. And so take us back to the research

you did to kind of give us a grounding in what we're

discovering here.

>> Susan: Yeah. So I have the

sense, I think it's a. I think it's a pretty good

bet that as long as there have been humans

gazing out over the ocean and maybe not being

able to see any other land, just as far as the eye

can perceive a horizon,

and thinking, what is it? What's down there?

Where does it go? How deep is it? And it's

amazing how long that went on, with all kinds

of wacky theories and beliefs. So

I did try to trace it back early, I

believe. Aristotle is often called the first marine

biologist because he did a lot of studying

of marine, creatures in a lagoon. And

he did it in a kind of empirical way and

learned a lot of things that he was the first

person that we know of to,

for example, identify whales as mammals,

all kinds of things like that. He was doing science

back then.

>> Jeniffer: Pretty good science, really?

>> Susan: Well, yeah. I mean, yes, absolutely. There was a

lot of, like, pliny the elder was talking

about myth and lore and

superstition and all kinds of things. But

Aristotle was, like, looking, finding things, taking them

apart, looking how they worked, making

observations that turned out to be, in a lot of cases,

extremely accurate. But I believe that

there have probably been humans that

are not in the western canon, or

culture in ancient Oceania.

certainly in, like, in Polynesia and

Melanesia, there are oceanic peoples that were

probably wondering about this

and parsing it as best they could,

way before Aristotle. That's my

personal guess.

>> Jeniffer: How could they not?

>> Susan: How could they not? And these are ocean people,

right. But, there

was, for a long time, the

idea of what was in the deep ocean was pretty simple to

wrap up in a single word, which was monsters.

>> Jeniffer: Monsters, yeah.

>> Susan: So when you think of the old maps, and maybe they even have

some, replicas of them in this library, when they

didn't know what was going

on in any patch of remote ocean, they would just put, here be

dragons, or here be monsters. But in 15,

38, there was a map printed that was created

by a catholic priest and historian from

Sweden named Olus Magnus. It's called

the Cartomarina. And if you've seen

drawings, these drawings of what they perceived as sea

monsters, you've probably seen the

Cartamarina. It's very famous. And so

I flew to Sweden to see an original copy of it. There

are only two that we know of, and it's really big.

It's like

23.

often when we see it, it's colorized.

But the original was not colorized, and the

colorized version kind of destroys it. The

real version in this huge, massive wall,

it looks like he drew it with a pin. I mean, he worked on it for, like,

35 years. And Olus's, job

was to travel around northern Europe and Scandinavia,

collecting for the church. And he had a

notebook and he had a sketchbook, and he talked to

people. And, if you can imagine

a 16th century medieval farmer

from Norway who's walking along

comes upon a stranded sperm whale,

you know, a 50 foot long animal with seven

inch teeth and an eye the size of a

hubcap. And, you know, what is it?

There's no context, of course, it's a monster. So

Olav's, Magnus really took a lot of trouble

to sort of categorize these monsters and he gave them all

names. And, so in his map, once you

get offshore, the north Atlantic is just

kind of frothing with sea monsters. so for me

it was a good place to start because along with being a

cartography of Scandinavia, which was kind of

an unknown part of the world at that time, it

was a beginning of a cartography of

perceptions about how humans considered the deep

ocean. That's where it began.

And then the enlightenment came along

and there were some instruments and there was a more

rational way of, determining science,

but that was really perplexing for the ocean,

and particularly the deep ocean, because

we weren't that far along with the instruments.

their sort of method was to take a weight, put it on a

line, on a spool, and

then let it go down to the seafloor and

just kind of sense when it hit the bottom and

then wind it back up and the winding it back up.

M the length of a man's arm is the measurement of

a fathom. So that's how they would determine, okay,

it's how many fathoms deep,

pretty, rudimentary. But

there were some incredible naturalists around

the 17th, and 18th and 19th

centuries, 18th, and 19th in particular.

And they started, sort of supposing

that probably there was nothing

down there.

>> Jeniffer: Yeah, the ozoic theory.

>> Susan: That's right. And it lasted for, they called it the

ozoic theory without life. And that theory lasted

for a really long time. Like,

it wasn't really completely dispelled till

1876. And even though

there were some people who were dropping weighted

nets to very, you know, to like, depths way

the ozoic theory basically said that anything below

about 2000ft, there was nothing there. And there were

people dropping trawl nets down to 12,000,

14,000ft. And the oceans

deepest, regions are, you know, can

be as almost as much as 36,000ft

deep, and coming up with all kinds of animals.

But some, some people hypothesized, some

scientists hypothesized that the seafloor was probably sealed in

ice, there was probably nothing there. And,

probably because we couldn't live down there and there's this

crushing pressure. And they knew that because if they dropped any sort

of, item with a cavity and it would come back

imploded,

some scientists felt that it was probably, the pressure

was so intense that nothing could sink. All the way

down, like, nothing was heavy enough to make it to the

bottom. So everything that went down,

ships, dead animals, humans

that fell off of ships were all kind of lost in space,

floating through the mid waters. And

all of this was dispelled,

like, 150 years ago.

>> Jeniffer: Right?

>> Susan: Yeah.

>> Jeniffer: Which is incredible.

>> Susan: It's incredible.

>> Jeniffer: And the cast of characters who did that.

Bibi, can you talk to us about him and his exploit?

>> Susan: So, let me just back up to

run into bb. there was a. The first deepsea

expedition happened from 1873 to

1876 and it was a british expedition

called the HMS Challenger that was, Queen

Victoria funded it, a warship that was kitted

out with science labs and they went around the world for three and a half

years, improved without a doubt that there

was life, really splendid life, all

the way to the bottom. And now we know that

there's even a thriving biosphere miles

beneath the seafloor, but

enough to dispel the zoic theory.

And so this was, they brought

back all these data and scientists from around the world.

About 70 different deep sea scientists and various

other disciplines spent 20 more

years writing a 50 volume set of here's everything we

know about the deep ocean. And it was

extraordinary. And one of the things that had puzzled them

was that a lot of the fish would come up,

glowing. They would have these sort of

circular, glowing, and they saw

bioluminescence sometimes on the surface of the water.

But they didn't know how any of these fish functioned

because when you bring a deep sea creature up to the surface, it really

just kind of looks like a deflated balloon. You can't

tell much about it, but they were puzzled by a lot of these

stranger looking creatures. So

now we're at the beginning of the 20th century

and, in 1930, the

man that Jennifer was talking about, William,

Beebe, he decided that he would be the first

man to go into the deep ocean. And by the

deep ocean, what he really meant was the twilight

zone, which is the uppermost layer of the deep

ocean and it goes from 600ft down to about

3300ft. and I call it the

Manhattan of the deep because

far from there being nothing living down there,

there are more creatures in the twilight zone than in all the other

regions of the ocean combined. And there are three

much bigger realms below the

twilight zone. But the twilight zone is just this happening

place with quadrillions, literally

quadrillions of animals in it.

And 80% of them are bioluminescent.

So that's the manhattan of the deep. Like, it's just this

blinking, flashing, throbbing,

like every eater be

eaten. night club of a place.

And Bebe was the

first man to see it. and he was a bit of a

celebrity in the 1930s. He was one of

the curators, at the Bronx zoo, which was brand

new. And he'd gone all over the world, to

collect exotic animals for the zoo,

and was very, very interested in the ocean

and was kind of a swashbuckling guy and a bit of a

celebrity around New York City. And also a

very, like, probably the most popular natural history writer of

his era. so somebody at one point,

Britain's Prince George just gave him an island in Bermuda

and gave him a ship, as one does,

and he be decided that he

was going to explore a two mile cube

of ocean in its entirety,

survey it, like find out everything that lived from

top to bottom. So he started trawling with nets, and

he very quickly realized that all the creatures came up

mangled beyond recognition. So he determined that

he wanted to go. He wanted to go. And,

this was of course, reported in the New York Times because he

was such a celebrity. Like BB is going to be the first man

to explore the abyss. And,

there was another man who was an engineering student in New

York named Otis Barton, who read this in the paper

and was very disappointed because he wanted to be

the first man to go into the abyss. But here's the famous

William Beebe. But Otis Barton had one thing that Bebe

didn't have, and that was a big trust fund.

And also Beebe, I think he was a scientist

and kind of a showman, and Barton was an engineer

and, could write checks. So,

he went to engage a naval architect and they created this

craft they called the bathysphere. And if you see

this bathysphere, you just cannot believe that two six

foot something men crawled into this.

It's just a steel ball with 5ft in

diameter. It has a hatch that's about six

inches wide that they had to squeeze themselves through.

It has three very, small

viewports, but they only ever used

two of them because the only material that they

had for a viewport was, fused

quartz or a very strong glass. And when

they, Barton ordered like five of them,

and when they pressure tested them, they knew enough

to know that they should pressure test them, but they didn't even pressure test them very

hard, and three of them immediately cracked.

So they had two. The only two that survived the pressure

test went on to the viewports, and the third

one was plugged with a metal cover. And the idea.

The thing is, the idea of a viewport blowing

out, which would, of course, never happen now, is

so terrifying because nobody knew exactly what would

happen. And this was a very, heavy

object, and it was going over the side of a ship on a

long cable. So, basically, a, two thirds of a mile long

steel cable, which also was very heavy.

If anything happened on either end of that

cable, they were on

a straight shot to the bottom, and that's where they

would remain. And they also. This is the part that

also cracks me up, is they had telephone wires running

in through this cable, and they're using

bottled oxygen to breathe. and, like,

if the sparks from the telephone

wires in an oxygen.

I mean, just. It's just like this when you read about BB. But

they did 30 dives. They did 30 dives. In a couple of

the dives, they sent the bathroom down, and they. And one of the

windows did blow out, but nobody was in it. And on one

occasion, the winch got tanked. They couldn't pull it up,

but nobody was in it, and they fixed things. So

I always kind of think of it as like a spin of

life's roulette wheel for Phoebe. But when they got

down to the twilight zone, he just. He just went

berserk. He was a really beautiful writer.

and he just saw these crazy,

beautiful, glowing, twinkling,

sinuous, gelatinous creatures.

And so the telephone line was for him to,

in this stream of consciousness riff, call up

everything he was seeing to this. He had, like, this bevy of very

attractive female

transcriptionists, and they all lived on

this island in Bermuda. So that was William

Beebe. but it left an astonishing record

of what lived in the twilight zone.

>> Jeniffer: When did you know you needed to write this book?

>> Susan: I wanted to write this book when I went to the Farallons and

saw that there was this massive party

in the ocean,

that you could not see. But

I also knew that I didn't

know enough and that it was the way

that I approach a book is I immerse myself.

And because I'm writing about the ocean, it's literal

immersion. And I couldn't get.

I couldn't crack that one way mirror, so

I went off. But I just started thinking about it all the time

and really amassing

information. And I'm very thankful that it

was my fourth book because it took

absolutely everything that I learned about the

ocean in order to be able to access

the immensity of this, not only the different there's

four different layers of the deep ocean. There's the twilight

zone that I just mentioned, the midnight zone,

which is, 1000 meters to 3000 meters. So

3300ft to about 10,000ft.

And then the abyssal zone, which is 3000 meters

to 6000 meters. So 10,000 to

20,000ft, give or take. And then

that's the abyss of the abyss is the largest ecosystem

on earth. Below that is, the hadal

zone, which is from 6000 meters to 11,000

meters. And that's named after Hades, the God of the

underworld. And the Hadal zone

accounts for 45% of the depth of the

ocean. But it only occurs in

trenches where tectonic plates

collide and one plate is subducting.

So the Mariana trench is one that people are

familiar with, but there are about 37 hadle

trenches. So there are these

extreme vertical environments. Like the Mariana trench

is 44 miles wide and, 1500

miles long. And, so it's just,

you know, it's a very steep

trench. and in each of those environments there

are biological sciences, geological sciences,

biogeochemical sciences. And I wanted to understand the whole.

And it's just a lot to bite off. I could not have done this as a

second book or even a third.

>> Jeniffer: Book or maybe anyone

else. I feel like you were the person to write this book.

>> Susan: I definitely was, obsessed.

I mean, I do think that books require a

certain degree of obsession because of

just the sheer volume of research

and particularly, of course, in nonfiction, and

in sort of a science adventure

travel, like. Yeah. in pursuit of a

story, I will go anywhere, do anything, read anything, go to any

trouble, as you.

>> Jeniffer: Will find out when you read this book. How long did it take you to

do the research?

>> Susan: Seven years.

>> Jeniffer: Okay. Which is really not bad.

>> Susan: And my other books have all taken five years and

Covid was thrown in there, so. Yeah.

Yeah. And it really helps to find amazing.

I always do look for really great characters,

particularly scientists or others who are

working and, studying in this environment,

sometimes interacting with it for other reasons who

are amazing guides.

>> Jeniffer: Yeah.

>> Susan: Yeah.

>> Jeniffer: Well, let's start with Kirby. Yeah, he was

an amazing guide who led you to your next

guide. And it sort of happened that way where one person

would open a door to another. So kind of bring us through

that.

>> Susan: So you're mentioning Terry Kirby.

I was living on Maui, and I had heard

through the grapevine that the University of Hawaii had

two 2000 meters manned

subs. They were called the Pisces.

And, the chief pilot was a man named Terry

Kirby. And we had mutual friends. So I went

over to Oahu to talk to him, saw the subs

and was just immediately like

taken by the sheer volume,

and the extraordinary content of the

stories that he could tell. And so the Pisces

could go to, could take, a pilot and two scientists

to 2000 meters, which is really pretty

good. there aren't that many subs that can go

very deep. There are only about

five, subs that can go below 4000 meters.

There were six before the titan imploded. But the titan

is a very extreme outlier. you can't even

really call it a submersible. It's more like

somebody's hobby that

tragically killed people. But, these subs are very,

very, very much a feat of engineering. They have their own

ships, they have their own crews of engineers.

they're serious, serious business. So having access to two

2000 meters subs and they weren't

at the time, accessible to dive because

their mother ship was, being

refitted. But one thing about submersibles

that's different than submarines is they need a mother ship.

They have to be, launched and recovered. And

when they're below the surface, they carry weight

that makes them negatively buoyant. And they go down

and then they drop some weights. The weights are usually steel

bars. Looks like phone books

or steel, pellets. But in any case, steel that

biodegrades against the background or the ocean.

and then they become neutral and they cruise around

for as long as the batteries will allow with thrusters,

their propellers. And then when it's time to go

up, they drop their major weight and

they're positively buoyant and they are recovered at the

surface of. I started to learn about

submersibles. I had started to learn

with Terry as my guide and a couple of his other

pilots. And they had been working in the Pacific.

And, the pacific is kind of my. It's

my muse. And there are hundreds of

thousands of submarine volcanoes.

75% of all volcanism on earth is

in the deep ocean. And Terry had been diving on

active volcanoes all over the place. And these

are not only geologically fascinating, but

like, biologically and microbially.

And, so I would just sit there and

listen, rap to his stories. And of course, they'd explored

all the world war two shipwrecks too, around Oahu,

when there are a lot of them. and he had found a

lot of them. So it was just story time.

but at one point it didn't

look like the Pisces were going to go back in the water anytime soon.

And I had already agreed to write

the book. My publisher was excited about it, and I was

still not sure, how am I going to get to dive in a submersible?

You just can't buy a ticket to do it. But then,

so we're talking 2017.

I heard that this company was going to build a 4000

meters sub. And I called them up.

They were called Oceangate. And

I said, they didn't have it, the sub, but they were like, we're

going to take people to the Titanic and we're not only going to build a

4000 meters sub, we're going to build a 6000 meters sub and

we're revolutionizing this. And I said, well, that sounds

really interesting. And then I went back to, this could be my

ticket to get. I don't want to go to the Titanic, but I want to

go to 4000 meters. So I get back to Hawaii and I

said to Terry, hey, I think I might dive in

this. This ocean gate sub. And Terry just

stopped in his tracks and said, and this is in

2017. You must never,

ever set foot in that sub.

because Stockton Rush had come out to the University of Hawaii with his

big plans and run them past

various people and wanted the university to get involved.

And it was from the start, like, just a

tragedy waiting to happen.

So I started a file, hoped I would never

have to use it. Ended up writing about it for Vanity

Fair in 2026.

>> Jeniffer: Wow. Yeah. Now, that wasn't in the book. You didn't?

>> Susan: No, because the book was published by the time this happened.

>> Jeniffer: Yeah.

>> Susan: The sub, tragically was lost

in basically what happened to the sub was what absolutely

everybody told him. What happened to the sub.

>> Jeniffer: Yeah. Yeah.

>> Susan: And so Terry and various. Various other characters in the

book, at numerous stops along the way of my

reporting, would say, like,

nobody really thought he was actually gonna do it.

>> Jeniffer: Right.

>> Susan: Yeah. And we prayed he would, but he did.

And, m. Yeah. So, yeah, the book came out

in. Well, the incident happened in

July. The book came out two weeks later, but

it was printed in May. Yeah. So that's also

why I wrote about it for Vanity Fair.

>> Jeniffer: There's a lot of things I want to ask you. And I realized we're coming up,

we're going to run out of time.

>> Susan: And that's the problem with the deep ocean.

>> Jeniffer: There's so much to talk about and read.

let's start with how much the ocean gives to us, because I think that's such

an important message in this book is that it's our life

force, and I don't think people are aware of that to the

extent. so talk to us a little bit about how much we

need our oceans.

>> Susan: Well, yes, I mean, think about, what I said

at the beginning is 95% of the

biosphere, right? Like, we know we live

on an ocean planet, but we live also on a deep ocean

planet. And the deep ocean, you know, I'll

speak about that. Just specifically right now, is the motherboard of

the planet. Of course, it's 95.

It runs the climate, it's the engine that runs the climate. It

is responsible. We knew, up until

very recently, we believed that 50% of the

oxygen. We knew that 50% of the

oxygen we breathe is created by phytoplankton and

plankton at the surface respiring in

photosynthesis. So the ocean is responsible for the fact that we

can be here breathing oxygen. But now, just

recently, they've discovered that there is also what they call

dark oxygen. There are,

metallic, elements on the bottom of the ocean

that act, emit small voltage

and split water molecules into hydrogen and

oxygen. So we're also, there's

oxygen being created at the bottom of the ocean,

and that's just kind of a sense of how much we don't know.

But every system that sustains us and keeps us

alive, I guess, you know,

obviously there are other elements like

the sun and the atmosphere, which keeps us from burning up,

but the ocean has

created the conditions for life to be habitable on

earth. It's where the carbon cycle is, it's where the

nitrogen cycle mostly is. It's

where 80% of the microbial biomass

of earth is. And I don't know how much you

guys know about microbes, but the more I learn about them, the more

I just am completely clear that

microbes run everything.

And so the ocean is this microbial,

repository, it is

the, as I said, the sediments themselves are

alive. And, it's this data bank of

genomic creativity that the earth has basically

archived in these living sediments. So

there really isn't much that

the ocean doesn't do for us all these services.

It is absorbing, about 90% of our excess

heat right now. We would be in real trouble if it

stopped. But we don't know where that tipping point

is. it absorbs about 30% of our excess

carbon dioxide. And the reason for that is pretty

wild. It's very complicated and

I'll simplify, but all those quadrillions of

tiny animals in the twilight zone. Every night

they swim up to the, hundreds of feet to the

surface and eat phytoplankton.

That has been. It's carbon because it's

been nourished by the sun. And then they swim back down

that same night. And when you're a fish this big, that's a long

journey. And excrete that, or

they're eaten by another animal, and that is then excreted.

And in that way, they are

cycling in a biological carbon pump carbon

out of the atmosphere and sequestering it in the sea floor.

And these tiny creatures sequester the

equivalent of America's total annual emissions.

>> Jeniffer: Wow.

>> Susan: and it's the largest animal migration on earth. and

it happens every day. It's a vertical one.

Yeah.

>> Jeniffer: Covid-19 part of the vaccination

came from the deep.

>> Susan: Yeah. So

from an enzyme in a hydrothermal vent.

And so hydrothermal vents are, in the

same way that when the plates collide, they subduct and they

create these trenches. And that subducting

plate is also where we get our major tsunamis.

When the plates are battling and one

slips, that's any earthquake over

eight has come from a subduction zone. And a lot of

them, if they're vertical, will cause a big tsunami like

the Tokyo one or the indonesian one.

but on the other side of the plate, the plates are

pulling apart and they're moving in both

directions, more or less at about the speed that your

fingernails grow. And, so when they pull

apart, magma comes up from the mantle and creates new

seafloor. And in the beginning, by the

way, kind of major thing, we only discovered it in, like,

1977. people were like, well, then

the earth is getting a little bit bigger every year. Well,

no, because on the other side of the plate, it's getting

subducting. Yeah. So it's in perfect equilibrium.

But on the new part, on the magma

comes up, there are hydrothermal vents. And the hydrothermal

vents, basically, gush out a mix of

microbes and minerals and elements from the

mantle. And, again in the seventies,

we discovered that life had a

completely new trick up its sleeve. Didn't need

the sunlight, didn't need photosynthesis. There were

animals all over the deep ocean

surviving instead on energy sources and

minerals, and microbes that were coming from

below. So just like I said, with oxygen, we've got this

top down source and a bottom up source. Same

with life. And I believe it's

probably the same with everything. In the ocean. But, yeah,

so the, these incredible

creatures, they call it

chemosynthesis, as opposed to

photosynthesis.

>> Jeniffer: Ah.

I mean, there's possibilities for cures for

cancer and many diseases, and there's so much that we

don't know about the deep. And yet

on the horizon, we're looking at the looming possibility

of deep sea mining. Can you talk a little bit about that? And how

extraordinarily

what a catastrophe that would be for our

planet?

>> Susan: Yeah. Well, one of the reasons why there is so much

potential, in these sediments is because these

microbes, the ocean for as many microbes as there are. And

I think the word that I came up with after asking your end

was nonillions, which is like ten to the

37th or something like that. there's

even exponentially more viruses, and

they're ancient. And so these microbes

have all these different metabolisms and these

different, strategies for dealing with

these being attacked by viruses.

I mean, on scales that we can barely, we can't even really

imagine. And, these are very novel

ways to approach things and that. And we are this,

they call it bio prospecting. And it's a very, very,

very young science. And we're learning that

there's this deep biosphere that goes even beneath the

seafloor. So the

seafloor that, let's just say 15,000ft, because

that is the abyssal zone. the hadal zone

will go deeper, but most of the earth is covered

by waters in the abyssal

zone. And when those waters hit the

seabed, they form something called the abyssal plain.

And it's very huge. It covers

54% of the earth. There are massive

geological features in there as well, like, giant mountain

ranges, all kinds of things you said, like.

>> Jeniffer: Mount Everest turned upside down in some cases.

>> Susan: Oh, dwarfed and everything. It's

just. Once again, I think it's really hard for us to wrap our heads around how

big it is. It's so immense. but

so, on the abyssal plain, there

are these metallic orbs that form,

and they're pretty widespread. And I wish I had a

picture. There's pictures in the book. they

look like little tiny cannonballs, but

they're not just metal. They're composed

of manganese, copper, cobalt and nickel. But

they aren't like lumps of metal. They're more like corals

or trees, because they're formed

by microbes, and microorganisms live inside

them. we don't know how microorganisms

form them we're kind of curious about that. They

accrete these metals from the seawater at the rate

of about like a 10th of a

millimeter every million years. So these things are

completely ancient. And they then

host an entire ecosystem on top of them. Because

they're on this sediment plain. So they're a hard

surface. So animals live all over them. Some of the oldest

lived and most interesting animals on earth

live attached to these nodules. So

since the seventies, this is the largest metal deposit

on earth. but it's in a realm that's very hard to get

to. And now we know enough about the

science of it to say it's kind of the womb of the earth.

It's one of the most stable environments. The water

is exceptionally clear. One scientist told

me the only more stable environment is inside a

cave. the abyssal zone. You can't call it

completely pristine because we have plastic and

nanoplastics. But we haven't been

down there monkeying around. But deep sea

mining is something that has been a glimmer

in the corporate eye for

decades. And It is not happening

yet on any kind of industrial scale. But

it's kind of on the verge of happening

now. And it's probably more complicated

than I want to get into about why. But let's

just put it this way. There are companies in some countries. But the

companies are the really bad actors. And they're hooked up

with Some of the small South Pacific nations that

are really desperate. Like in particular this nation called

Nauru which is 8 sq mi.

And These companies can't mine the seafloor without

the sponsorship of a country that has

signed the treaty of the law of the sea. And

with Nauru's help, this one company called the

metals company has forced this

issue forward to the point where the entire world

has gotten involved. And it's just a

battle. And what they plan to do

is Destroy a 2

million square mile area between Mexico

and Hawaii called the clearing Clifford zone. And it

would be like clear cutting a forest but taking the top

20ft of topsoil too. They would take all

of the nodules, all of the living sediments

beneath them. and this is really

not. This is dredging technology. It's going

to cause a giant

cloud that will kill every animal. Because

the water is so clear. They've never evolved to dealing with

any particulate. They will then shoot everything up

a three mile pipe. And it's animal and mineral,

right. Because it's everything that lives on the nodules. There's no

plants in the deep ocean because there's no

photosynthesis. So animals, minerals up

the pipe, they would then separate

out the nodules and then blast everything

else, down and release it in

a continuous fog at

1200 meters, which is the area of the twilight zone

and midnight zone, where all of the animals

communicate, hunt, mate, do

everything with bioluminescence. So

it's the like, of all the things that we do

that I don't like in the ocean, this just

dwarfs. But here's the good news, and

I really think it is good news. I think it's too

insane, even for us. This is the biggest carbon

sink scientists have banded together to say, look, we

need at least 30 years more

study because we don't know what we're even destroying.

And it's not going to grow back. When they're

gone, they're gone, the microbial services

that are happening. But the greatest thing that

happened recently to prevent it from happening was that they realized

that these nodules were actually the ones that are splitting the

water molecules. So these nodules are creating oxygen.

>> Jeniffer: Yeah.

>> Susan: oxygen. Oxygen, yeah.

And so that's a real stick in the

spoke of these companies that want to rip them up.

But it's just also their idea is

that we need nickel and cobalt for ev

batteries and for a greener future.

Let's destroy this last. I mean, the thing that's

keeping us alive. but now the battery

chemistries are moving away from cobalt and nickel, so there really is

no reason to do it.

>> Jeniffer: So there's hope.

>> Susan: I actually think this is a battle that we will win, and I think

it's a pass fail test for humanity, and I feel

very optimistic that we won't do it.

>> Jeniffer: Nice. Yeah, I'm glad to hear it. So, yeah, I

want you to tell everyone about your deep

experience before we run out of time.

>> Susan: Okay.

>> Jeniffer: well, and I wish we could talk about Victor. He's my

favorite.

>> Susan: Well, I will. Victor,

I wanted to get into a submersible, and I, got

in nonfiction. You set out to write about a

subject, a story, and then you go out

reporting, and so there's a certain amount of

serendipity involved, and, like, who do

you meet? What do they tell you? What do you

find when you really look? And so

I will come right out and say, I think there's an element of luck

involved. And this book, I got

extremely lucky because as I was

kind of sulking after being

told I couldn't dive with ocean gate, I couldn't figure out

anybody else. I could dive with the Pisces right over the water.

And I heard about an expedition that was

going around the world to go to all the deepest

places in every Hadel trench. And

I immediately started asking around,

found some people that I knew through my. This is why I say

it really took me all the books

to be able to write this one and got an introduction

to the people that were doing this expedition. And it was

all, at

the auspices of a man named Victor Vescovo, who

is a very interesting character from

Texas. And Victor is a guy who's made quite

a bit of money, although he's not a billionaire.

we kind of invite billionaires to spend their billions

on ocean research because the government doesn't do it. It

gives like a dollar to ocean research for

every, every

dollar, for ocean research, NASA gets

150. So there are a number of very wealthy

individuals who have

sponsored, science expeditions and have their own ships and have

their own subs and have their own robots. And it's,

as far as I'm concerned, all the better. More the

merrier. Victor wanted,

to go to the deepest spots in the ocean

because nobody had ever been to them. And

he, had been to the top of every mountain range, and

he had skied to the north and south pole, and he was looking around for something to

do. And he, is a very smart

guy. He's almost like a

Vulcan, kind of, but with like,

he's not your average texan. He's got a long, blonde

ponytail, and he's kind of like, looks like a raptor. And

he's almost Asperger's because he's so

smart. And, he found the best

company to build this sub.

>> Jeniffer: One of my favorite things, he says, is for relaxation. He

studies military history. History. I was like,

okay.

>> Susan: Speaks seven languages, including Arabic. It was in

naval intelligence, doing, I forget what.

It was like some crazy thing where they locked him

in a room in Pearl harbor,

like, trying to analyze stuff for 20 years. and

he, ah, found this company in Florida

called Triton submarines. And I always refer

to them as the apple of submersible design. There aren't that many

submersible companies, but Triton is just

magnificent. And so he caught the right,

and nobody thought there could be a fullish in depth passenger

submersible. It had been tried before James Cameron tried

it in 2012, and his submersible

basically started to disintegrate on the bottom of the

Mariana trench. he won't tell you that, but I'll tell you

that. And I know people that were on the

expedition and he. Eleven, of his twelve thrusters

failed. He couldn't go anywhere. There were cracks in it. It

never dived again. Victor wanted one where he could take

a scientist, and it

could dive repeatedly, safely,

to the greatest depths that nobody had ever been

to. And the great thing about Victor was

that he brought all the top hatel

scientists along and bankrolled it all. Although

Victor's not a billionaire, like he actually had some,

as wealthy as he is, incurred quite a bit of personal

risk. and it was an expedition called

the five deeps. and so I actually

just kind of got invited onto the five deeps.

>> Jeniffer: Awesome.

>> Susan: And it's just a massive stroke of

luck. And also to be able to meet the top scientists

in the hadel zone. And also I love

scientists because they're so passionate

about what they study. These scientists had dedicated

their lives to studying this realm that they had never

seen. And Victor started taking them down

and every dive was just this massive

revelation. And so once

that expedition was over, he decided to keep

going. And so there was another expedition called

Pacific ring of fire. And I got

onto that one. And then at some point, I

asked Victor very nervously,

do you think I could maybe dive with you sometime?

He knew I was writing a book and he turned to me and

said, sure, let's go to the Mariana

trench.

And I won't do any spoilers,

so I got to do, As far as I know, I'm the only journalist

that got to do this because Victor then couldn't really

afford to keep the sub in the ship and sold it to,

It has a very happy ending because it was sold to a man named

Gabe Newell, who was, I think, number,

three at Microsoft at one point. And Gabe is

obsessed with the ocean and hired all the Heidel scientists

and basically gave them the sub and the ship. So

now that that sub and ship just goes around the world doing

science funded by a billionaire, it's pretty awesome.

And sometimes people get really edgy when I mention this

because like, there is a Google, Eric Schmidt has the ship,

Ray Dalio has a ship. And people think this is really awful,

but it just. The ocean needs,

they have these resources and let's

get them for the ocean. We need this.

>> Jeniffer: One, hundred percent.

>> Susan: And to dive that deep is just

extraordinary. The best way

I can say it is. It's

like meeting the earth for the first time

and it's awe

and the ocean. One of the

things I love most about it is that it

requires humility. A real, true

humility, because you really understand

life from a different perspective. and

I come back with as many details as I

can so that I can share them with readers, and we can all

revel in this experience. But I will also say that

if you ever have a chance to dive, first of all,

make sure you're in a sphere. Has to be a sphere. That is the only

shape that. That can withstand the pressures and distribute

them equally.

>> Jeniffer: Tell us about the egg.

>> Susan: The egg. well, one of the. They sent an egg down. An

egg survived the Mariana trench.

>> Jeniffer: Outside. Not inside the sphere.

>> Susan: Outside the sphere. Think of it. It's like if you take a sphere and you

crush it, it just becomes stronger. If you step on a coke can, you

know what happens? The sphere is the shape. And, all

of these subs go through like a much

a, very expensive, very rigorous testing

that's akin to the FAA, but much more

involved, more like NASA, probably.

again, the only sub to have ever

skipped that step was the Titan. And that's

why the realm of Manson

Mercibles has 100% safety record.

Outside of that tragedy. the

only sub that would go to full ocean depth was Victor's sub

until 2023, when the

chinese government created a three man sub.

so there's only two of those in the world. and it

just. It just can't fail to

change everything. Like, emotionally,

psychologically, spiritually. It feels very

serene, but also, it's very serious. You know,

it's very serious. You can feel the gravitas of

it, but it's serene.

Yeah.

>> Jeniffer: And you can feel it so well in the

book, reading your words, it's such a beautiful experience. I

hope everyone will read this book.

Let's open up to questions. Does anyone have any

questions for Susan?

Oh, hi there.

>> Speaker C: I'm sort of curious about how

much money it takes to launch a

rocket up into space. What is the

comparison of the cost to create

these submersible?

>> Jeniffer: Good question.

>> Susan: Yeah. Victor's, submersible,

they all need a mothership, so that adds the cost.

And, Victor's sub was, I think it cost about

$80 million. And then there's the operations.

Like, for every hour they dive, they need about two and a

half hours, 3 hours of maintenance. And, you know, the environment

is just unlike space. It's incredibly

the, pressure. I mean, at the bottom of the Mariana trench, the pressure

is, 20,000 pounds per square

inch. Which one person,

told me is the equivalent of 307 seven

s fully fueled, stacked on top of

it. So that is not an issue that you're going to have

in space. And you need the same kind of a controlled

life support system because every. So, like a lot of the

times people will say to me, well, how do you decompress? Do you need a

decompression stop on the way up? And it's like, no,

that sphere has got to be unbreachable. That

one is four inches of titanium. In

a perfect sphere, it has to be perfect.

and I mean, the trouble that they go to, to build this,

it's just such a feat of engineering. And to give you a

sense of how, I mean, between

2012, when James Cameron became the

third man in history to go down to the bottom of the

Mariana trench, and, sorry, between

1960, when two men for the first

time, one from the navy, one who was

a swiss physicist, went to the Mariana

Trench in, a craft called a bathyscaph,

between then and 2012, when James Cameron

went, that was three people. During that same

time, something like 250

people went to the international Space Station. So it's

a really. The engineering

costs and problems caused by the

saltwater itself and the pressure,

I, think, make it more expensive over the. I

mean, there are three Mars rovers

and two full ocean depth submersibles.

>> Jeniffer: Yeah. And it's like almost all privately funded,

which is just insane to me.

>> Susan: Yeah. The government doesn't fund any manned. Well, no, that's

not true. the national science. There's one, sub

that I dived in fairly recently called the Alvin. It's the US

Navy's research sub.

>> Jeniffer: That's the one on the COVID Yeah.

>> Susan: And, that's it, though. And scientists wait a really long time

for that sub. It's the only sub that we have that does

research. the other tools that they have are

really capable too, like Rov's.

They're really useful for certain things. They can take

amazing. they have fiber optic cables, so you can

get amazing. You can send them into places that are too dangerous,

perhaps, where, you know,

in a place where you might not be able to get a

sub, a sub might get trapped or something.

There are autonomous vehicles. we are just. We're

living through a golden age of finding out what's down

there and science has everything to do with it.

Yeah.

>> Speaker C: My concern would be how did

China, come get involved in

this? Because that's my concern would

be what their reasoning or

desire is to do this and it wouldn't be

just empirical research.

>> Susan: You're quite right. They're all about mining.

you know, it's a little bit like

enervating to know that the US,

does not have any full ocean depth assets.

China does now. And one time when Victor

dived into, one certain area of the

mariana, Victor ended up diving 15 times into

the Mariana trench, into the challenger deep, which is the

deepest spot, and took down twelve

different people, including the first female,

scientists. And, one thing that they found when

they were down there, because nobody had been there,

was a whole bunch of fiber optic cable.

and keep in mind, he was in Navy

intelligence for 20 years, and he believes that

the chinese government is using some of their full ocean

depth assets to put listening devices at

depth that nobody else can, find

them. And that they knew that the sub was

coming and would be traversing the trench. And so they

cut the instruments and left the cables. Leaving

cables as entanglements is one of the most

dangerous. Subs

don't implode. Except for the titan, subs do not

implode, but they get entangled in cables

sometimes. so that was kind of crazy.

And, china has something like ten,

ocean research vessels, and they

also have two subs. One goes to

6500 meters with three people, and the other one

goes to, I think, 4000 meters. So we have one

6500 meters sub, they have

111 thousand meter sub, one 6500

meters sub, and one 4000 meters or 5000 meters

sub. And, they have ten. They also have,

like, a whole chain of ocean

universities. They are playing the

long game and investigating the deep ocean

in a way that America is absolutely not

doing. And, I hope that

changes.

>> Speaker C: I'm hoping that even if the government isn't, our

government isn't willing to fund that. They're being

apprised of that and have the

understanding of what the potential could be if

they don't m put that on

their, wish list or to do list that they

need to. I mean, space travel is fine,

but.

>> Susan: This is where we live, right?

>> Jeniffer: Exactly.

>> Susan: Oh, man. yeah, no, I

don't want to.

>> Speaker C: Be or be behind China on

anything related to our survivability here on

earth.

>> Susan: Right. And, you know, if

something happened, one of the reasons we have the

Alvin is because a submer,

two. Let me see if I get this right.

two us planes, a B 52 bomber and an

aerial refueling plane, ah,

collided over the Mediterranean and a

hydrogen bomb fell into the Mediterranean at a depth

that we, and I think this happened in like the

fifties. Don't quote me, but it's around that era.

and there was no vehicle

of any kind that could get this out

and you couldn't just leave it lying around there. so

they created the Alvin. so we do have this

one sub and we have some pretty good rov's

but the French have a 6500 meters sub, the

Japanese have a 6500 meters sub. The only

subs for the Heidel zone are Victor sub, which

is now privately owned for scientists

and hasn't got the ability to

do the heavy duty science work like,

installing instruments or recovering instruments. It's more

of an observation and has a manipulator on for taking

samples of sediment and fauna. But like

some of these subs, like the Alvin have,

it's like going down with a portable, like,

garage.

and the chinese sub is so big it

travels with its own crew of 80

technicians.

>> Jeniffer: It's crazy.

>> Susan: It's got a bathroom in it and believe me, they

don't have bathrooms. And So

yeah, if anything happens

below 6500 meters, any of

our assets, anything like that, we have no ability to get

it. Not even an rov. We

don't. But Woods Hole is working on this and they may have some

Rov's soon, but it's an astonishing

gap in security, I think. And especially when

you consider that all of our information runs

through seafloor cables and there

are hundreds and hundreds of seafloor cables and

those are incredibly easy to access if you can go

down there and do it right. Yeah. So

that's a very interesting point. Yeah.

Thank you.

>> Jeniffer: And with that, I think this gentleman. Can I

get one more question? Yes, sir.

>> Susan: It just seems hard to believe the navy with all of our submarine

force are not studying all this and have

no motivation to do that.

>> Jeniffer: It seems incredible.

>> Susan: Well, they have woods hole and they have scripts

and yet it's the vehicles and, you know, a

submarine. we don't know exactly what depths the subs

go to, but let's just say it's.

Russia had a sub that could go down to 20,000ft. It was called

the loric and Russia had some very

strange subs and the Lashark was like a pearl necklace.

So sphere, sphere, sphere, sphere with tunnels between

them and something happened to it. I think it

caught on fire and they all died. And of course it was

completely secret. It could be that the US has

some vehicles like that, but I think I

would know about them. Actually. I have

some pretty good contacts, and it's confirm or

deny kind of thing. But,

the submarines can't go very deep. They really can't.

Like, I would say 600.

It's not a submarine thing. It's something else.

>> Jeniffer: Yeah.

>> Susan: Yeah.

>> Speaker C: Well, I would just add on there, I'm retired from the

Navy. But my feeling would be is it's not that the

Navy's not interested. It's also an matter of

funding.

>> Susan: Yeah.

>> Speaker C: And if you can't get that point across,

because that's the first. I'm so glad I came,

because I have no understanding of this at

all. And this is serious and

feels very serious.

>> Susan: Yeah, totally agree.

>> Jeniffer: It is very serious.

>> Susan: It's 95% of the planet.

Victor is a great emissary for this. You

know, he's still, I

guarantee you there are people in the Navy that have, he's

debriefed. Yeah.

>> Jeniffer: Well, please buy a book. Get it signed by

Susan. She's gonna be in the back.

>> Susan: And.

>> Jeniffer: Thank you. Oh, she's gonna be signing up here.

>> Susan: Yeah. Oh, shoot.

>> Jeniffer: All right. Can people get up here?

>> Susan: Thank you so much for coming.

>> Jeniffer: Okay. Yeah. Thank you.

>> Susan: Thank you. Jennifer.

Creators and Guests